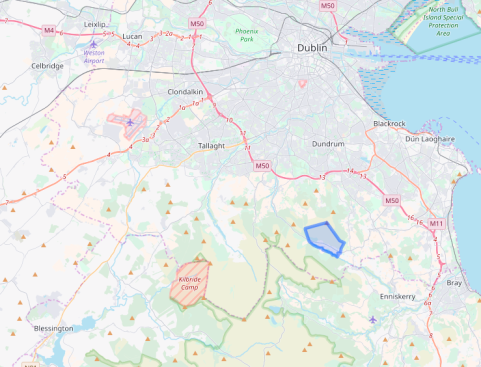

Ballybrack townland is close to the Wicklow county border in south Dublin (fig. 1). Its boundary encompasses an expanse of upland heath strewn with innumerable granite boulders and outcrops. Turf cover is thin, and at the lowest elevations, rough pastures provide occasional grazing. The townland is roughly basin shaped with flanks to the east and west rising up to create the backdrop of Two Rock mountain (536m OD). The two flanks embrace the warmer aspect of the southwest, and evening sunlight persists here for much longer than in the populated district below.

The Fairy Castle on the summit of Two Rock is a substantial cairn that is widely understood to house a passage tomb (plate 1). Views from this summit are exceptional: the plains of Dublin, Kildare, and Meath are laid out below. All of the Dublin bay islands are visible; as is most of the Irish Sea coast to the north, and south to Bray. The Mourne mountains can be easily seen most days, and the associated Dublin/Wicklow passage tombs and even the mountains of Snowdonia – weather permitting. Below and to the south of the Fairy castle, the land falls quite gradually in a series of undulating terraces down towards the Glencullen river.

This place has had a distinct appeal to this visitor for many years, culminating in a formal examination of the work of the many generations of stonecutters who worked granite on these hillsides. They cut the granite by hand, and supplied roughed out orthogonal baulks to the Dublin stonemasons (plates 2 & 3). This raw material was ultimately fashioned into the street furniture that gives the city so much of its rapidly vanishing character; the paving slabs of the Georgian squares, steps, wall copings, window sills and so on. Many of these undervalued things came into being on these hillsides. Prior to, and during field work for that paper, it became abundantly clear that there are substantial quantities of extant prehistoric remains distributed throughout the townland. One of the most interesting appeared out of the mists some years ago. It is a massive, well weathered granite boulder supported at the back by three granite slabs laid flat, one on top of the other. There are two upright stones or orthostats that elevate the front, and a third appears to have been dislodged. Beneath the capstone there is no distinct chamber or any other form of internal division.

This was not the first time that the structure had been identified. The arrangement was first recorded and illustrated in 1852 by the artist and antiquarian Henry O’Neill (1798 – 1880) who wrote:

‘On the hill at the Dublin side of Glencullen I discovered a rock monument. The roof rock is ten feet long, eight feet broad and four feet thick, extreme measures; the longest direction of the roof rock is W.S.W, or nearly E. and W. The chamber is greatly disarranged’ (1852:43).

The ‘rock monument’ today fits the dimensions recorded by O’Neill, as does its morphology, except for the missing blocking stone (extreme left in figure 1).

Portions of the structure have become obscured by the blanket bog since O’Neill’s impression – or he may have taken artistic liberties to emphasise its megalithic presence. It is probably more of a surprise that any of its components survive at all, given the scale and duration of stone exploitation on this hillside. The wedge tomb at nearby Ballyedmonduff (and at approximately the same elevation) was partially robbed out by the stonecutters. On the other hand, the absence of signs of exploitation could underline the possibility that the monument was known to the stonecutters, and afforded some protection by the lore that has saved so many of our monuments.

Forty-five years after O’Neill published the engraving, William Copeland Borlase supposes that:

’In the town land of Ballybrack, adjoining that of Ballyedmonduff on the SW and Parish of Kilgobbin, is a dolmen marked Giant’s Grave in Ord. Surv. Map No. 25. It is half a mile WNW of Glencullen House, a quarter of a mile N of the Glencullen river, on the NE slope of Two-Rock mountain, the sides of which latter are covered with circles and tumuli. I suppose this is the same dolmen to which Mr. Henry O’Neill alludes as being on the Dublin side of Glencullen.’(1897:388).

From this point onwards, the whereabouts and existence of the monument becomes distinctly problematic, and largely ignored. Borlase’s directions pinpoint the Giant’s Grave site with some precision; O’Neill’s description by contrast, is decidedly vague. ‘…the hill on the Dublin side of Glencullen…’ amounts to most of the side of a glacial valley and encompasses an area of about eight square kilometres. Both O’Neill and Borlase reported on the ‘rock monument’ some time after the ‘Giant’s Grave’ had vanished. When Eugene (O’) Curry visited the locality in 1837 to gather information about local antiquities for the Ordnance Survey, he recorded the following:

‘The Giant’s grave at Ballybrack is but little known, though it appears to have been partly opened, but not within the memory of Peter Welsh, who lives near it, and is now 90 years old. It is situated on the top of a little cultivated hill and covered with a stone 10 feet by 7. No person in the neighbourhood ever heard any name for it but Peter Welsh, who when he was a boy heard the ould Irish people call it LEABA NA SAIGH (the greyhounds bed). This name must have originated in one of those popular fireside stories about spirits appearing in the shape of greyhounds etc.’

(14 C 21 49/50, Letter from Eugene Curry to Lieut. Thomas A. Larcom 13th July 1837).

The crucial fact at this point is the mention of Peter Welsh’s proximity to the Ballybrack Giant’s Grave. Griffith’s valuation records a Walsh household just a few fields away from the site in 1849. The surname Walsh is often pronounced Welsh, so it may be reasonable to conclude that this was the family home of Peter Welsh/Walsh and that the nearby monument he described as Leaba na Saighe is the same one depicted on the first edition map. There is no doubt that Welsh’s Leaba na Saighe and O’Neill’s ‘rock monument’ are two entirely separate features. This is emphasised by Paul Walsh of the Megalithic Survey who notes in the entry for DU025-044 that a number of other writers ‘incorrectly assumed that the O’Neill site and this monument were one and the same’ (National Monuments Service 2014). Without visiting both sites, it would be an easy mistake to make. The essential arrangement was similar in both instances, the dimensions were very similar, and they were relatively close to each other.

Ballybrack is an Anglicisation of an Baile Breac or the Speckled Town. The speckling probably refers to the masses of bleached granite field stones (‘wild stones’ in the stonecutters’ vernacular) that stand out against the muted hues of heathers and bog. Almost every one of these stones seems to have been exploited by stonecutters, and there are many places where their work has left unlikely arrangements of stone; some of which resemble megaliths or other forms of prehistoric stone construction. A recent visitor to Ballybrack saw one of these formations, assumed it was O’Neill’s monument, and forwarded their findings to the Monuments Survey (pers. comm. Paul Walsh). The feature they saw was either natural or a by-product of stone-cleaving. It was an easy mistake to make. Some of the formations, especially where stonecutters exploited massive slabs, have a morphology that could easily be misinterpreted as a megalithic structure (plate 4).

The monument is now recorded as a ‘megalithic structure’ (DU025-088). To what class it belongs is another matter. In overall form, it is probably closer to a boulder monument than any other monument type. The roof boulder is set on three or more support stones, all are less than a metre tall, and there is no surviving evidence for the existence of a covering cairn or any clearly defined chamber on the interior. These criteria fit well with Ó Nuallain’s observations on the morphology of the Cork and Kerry boulder burial group (1978, 76-77).

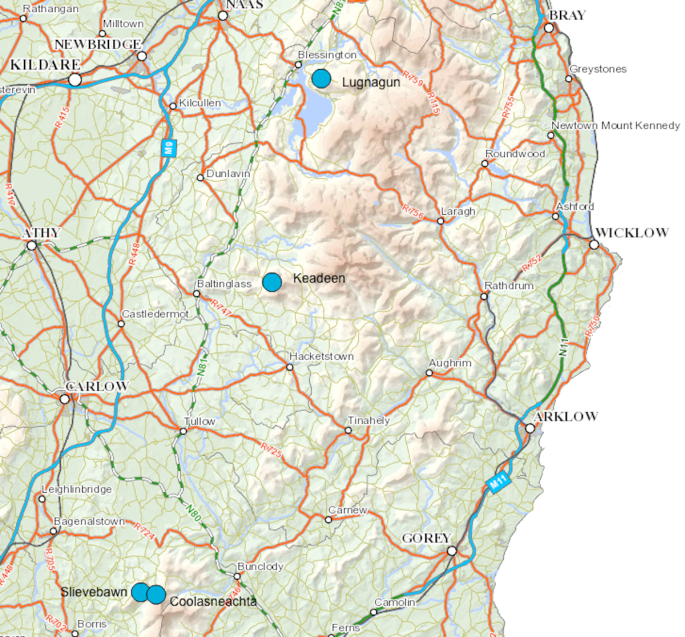

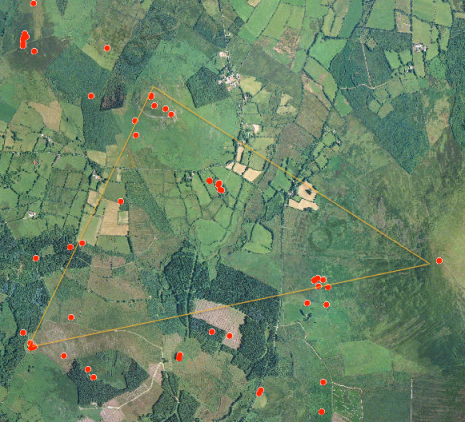

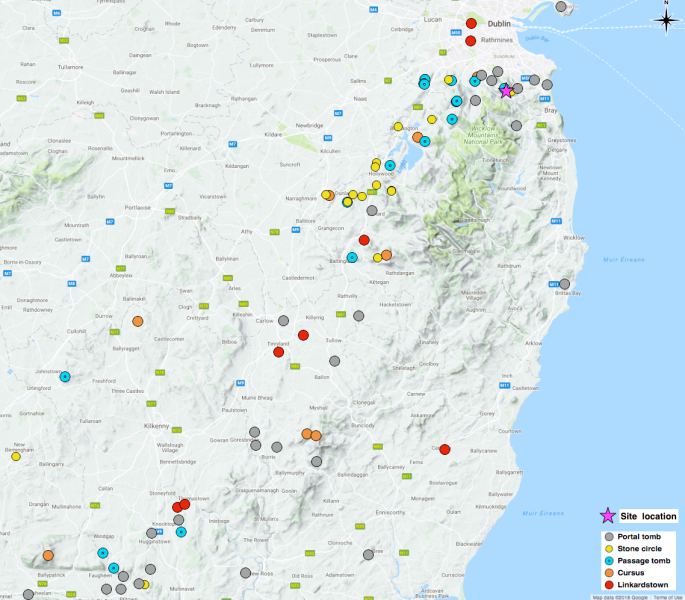

Boulder burials are predominantly concentrated in south west Ireland and are typically associated with the Bronze Age (see also Roaringwater Journal for a discussion on the term burial). There is just one boulder burial recorded in Leinster: at Motabeg near Enniscorthy, county Wexford (WX026-014). However, there appears to be a clear pattern in the distribution of a range of megalithic classes in Leinster. There is a distinct concentration on the west and north-facing edges of the Leinster massif (Fig. 2).

It is highly probable that this concentration is a consequence of deliberate situation with views to or from the north and west with intervisibility of the monuments, rather than simple survival. The western edge of the Leinster massif has been subjected to just as many intrusive cultural activities as the east and similar monuments, had they been built there, would just as likely survive today. Taking these hypotheses into account, it is possible to see that the rock monument fits very well into the overall distribution pattern. Of course distribution offers a limited insight into the situation or nature of an individual monument but in this case it does at the very least indicate that we should not be surprised to find a similar monument in this area.

In conclusion, O’Neill’s rock monument became confused with a similar monument that was once nearby. This happened for a variety of reasons that ultimately led to an assumption that the monument was lost, never existed, or had been misinterpreted in the first instance.

The monument survives intact and is almost identical to the one illustrated in 1852. It is a difficult monument to classify because it has elements that belong to several classes. The massive capstone is reminiscent of the enormous effort required to raise a portal tomb capstone, but the arrangement of supporting stones disallows that classification. Its arrangement and overall morphology fit well with the typology of boulder burials, but it would be an outlier in the distribution of that monument class. However, the possibility that it is a boulder burial is not necessarily precluded by how it fits into the distribution pattern. The context too, may provide support to the belief that this is a boulder burial. The surrounding landscape contains a considerable number of closely associated monuments and features that are almost certainly Bronze Age in date (Kenny 2018 forthcoming) and boulder burials are widely thought to fit within that period (plates 5 – 7).

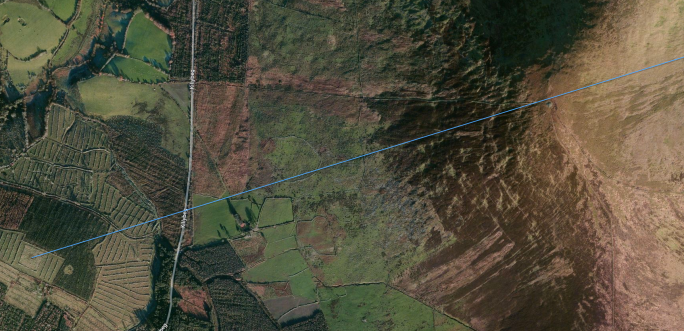

As a post script, one other feature of the monument should be mentioned. A groove on the upper surface of the capstone is strikingly similar to a possible solstice alignment identified by Brigid O’Brien (Finlay 2016). The groove on the Ballybrack capstone aligns with the winter solstice setting sun at a point on the horizon above the origin of a watercourse (plate 8). The groove is too eroded to determine if it was cut or naturally formed but in either case, it may have influenced the choice and orientation of the roof stone.

Further reading;

Borlase, W.C. 1897 The Dolmens of Ireland. Vol 2. London.

Finlay, F. 2016. Boulder Burials: a misnamed monument? Roaringwater Journal. Available at https://wordpress.com/read/feeds/13587098/posts/1005975143

O’Donovan, J. Petrie, G., Du Noyer, G.V. et al, 1837. Ordnance Survey of Ireland: Letters, Dublin. MS 14 C 21 49/50 Letter from Eugene Curry to Lieut. Thomas A. Larcom 13th July 1837

O’Neill, H. 1852 The Rock Monuments of the County of Dublin. Transactions of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society, Vol. 2, No. 1. Pp 42 – 46.